A Los Angeles Times headline in 1995 asked, “Can the department store survive?” A quarter century later, CNN proclaimed that “America has turned its back on big department stores.”

These are just two of many obituaries predicting the imminent demise of the U.S. Department store—and all that pessimism has been backed by the data. Department stores have been losing market share for decades, first to big-box discounters like Walmart and Target in the 1980’s and 90’s, and more recently to Amazon. The department store’s percentage of total U.S. Retail sales has fallen from about 14% in 1993 to only 2.6% last year.

But now, perhaps improbably, there are new signs of life in the retail format, with growth this year at Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s, Dillard’s, Nordstrom, and Belk—and signs of stabilization at J.C. Penney and Kohl’s.

The path that department stores are taking back into shoppers’ favor is a return to what made them popular in the first place: well-maintained and attractive spaces with attentive staff, a well-chosen selection of products, and enticing new brands. Many chains are finding that fewer stores are better, and have been shutting down locations to maintain quality and brand congruence.

With most products available online, often at lower prices, department stores must offer some real value to the brick-and-mortar shopper. But it’s an uphill climb to reverse some of the erosion of standards that have diminished the appeal of department-store shopping. Competition with the Walmarts, Targets, and T.J. Maxxes of this world led many department store companies to cut corners and skimp on retail flourishes, eroding their raison d’être in the shopper’s mind.

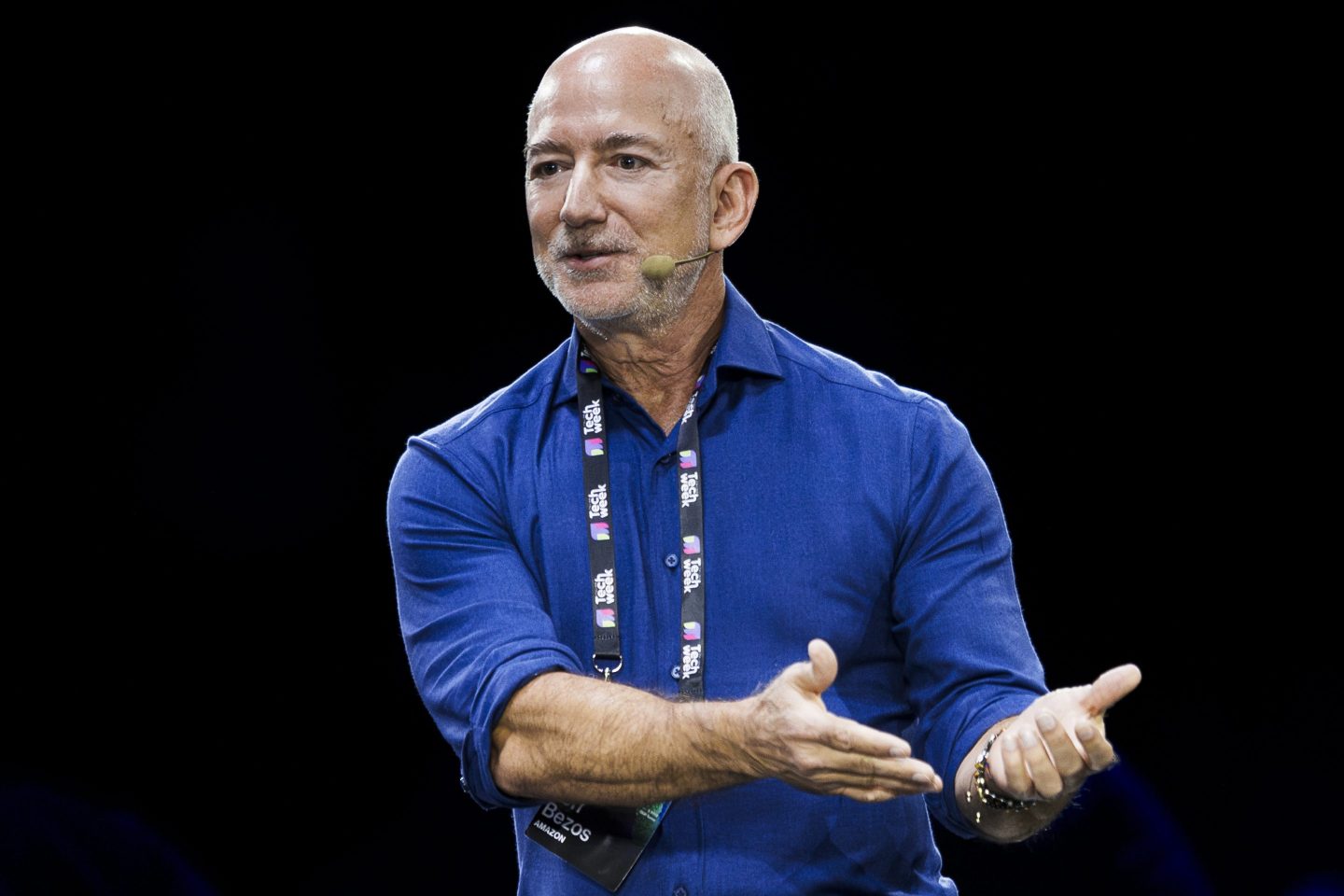

“You know what was tough about department stores?” Macy’s Inc. CEO Tony Spring recently told Coins2Day. “We didn’t execute well. A bad store, no matter what you call it, is going to fail.”

A string of bad seasons

And indeed many did fail. In 2020 alone, Neiman Marcus, J.C. Penney, Lord & Taylor, and Bon-Ton Stores filed for bankruptcy protection. They were already struggling before they were pushed over the edge by a pandemic that kept shoppers away for months. A couple of years before that, Barneys New York and Sears did the same, eventually going out of business altogether.

As Spring told Coins2Day, Macy’s recent success—including its best quarter for sales growth in three years—is thanks to a playbook focused on less store clutter, a more focused assortment of products and brands, and more staffing in key departments such as women’s shoes and dresses.

Rival Dillard’s, a primarily Southern and Southwestern chain with 290 stores, has also seen modest growth by following those basic retail precepts. Unlike many of its mall-based peers, Dillard’s has rarely deviated from its formula of neat stores and thoughtful product discovery, and is roughly the same size today as it was 15 years ago by revenue and store count—unlike chains that expanded rapidly, then closed scores of stores.

Another department store that appears to be staging a comeback is Nordstrom, which went private this summer to revitalize its business outside of Wall Street’s glare. It has seen sales rise 4.1% in the first half of 2025. Belk, a privately held Southern chain, is seeing growth too, though more modest, according to industry estimates.

Still, it’s too early to pop the champagne. Dillard’s and Macy’s modest comparable sales growth of about 1% last quarter is hardly the mark of a roaring retail renaissance. And Penney and Kohl’s are still seeing sales declines, albeit less severe than just a few quarters ago.

Meanwhile, some companies are still deep in the doldrums: Saks Global recently said its sales fell 13% last quarter. In that case, the decline is largely because vendors are not sending it enough merchandise given recent delays in getting payment from the debt-laden company. Clearly, department stores are not out of the woods.

Catering to the bargain-seekers

The holiday season, during which department stores get nearly a third of their annual sales, will be a major test of their nascent comeback. The Mastercard Economics Institute has forecast that sales will rise 3.6% November and December, a slower clip compared to last year’s holiday season. And shoppers are likely to be particularly bargain-hungry, meaning they will be holding out for deals, a trend department store executives are already seeing.

“Many Americans are more stressed than ever about holiday spending, and wallets are stretched,” JCPenney chief customer and marketing officer Marisa Thalberg said in a recent presentation of the retailer’s holiday season strategy. The company’s response? To offer more deals, and earlier in the season.

Kohl’s Chief Marketing Officer Christie Raymond expects shoppers will visit stores more often during the Thanksgiving to Christmas period, but buy less during each visit and gravitate to cheaper products as they feel the economic pinch.

“We are seeing trading down,” Raymond said at a media briefing in October at Kohl’s design office in Manhattan. “Whereas some customers were maybe purchasing a premium brand, we are seeing them trade down to private brands.” This could bode well for the success of Kohl’s recent efforts to refresh its long languishing store brands.

Even the high-end store Nordstrom, with its well-heeled clientele, is emphasizing more low-priced items than usual this year. At its New York flagship, Nordstrom has built a two-story area to showcase giftable items, with about 800 products that cost less than $100.

Back to the future

A century ago, department stores began a golden age in which they were at the forefront of America’s burgeoning consumer economy. They were grand behemoths, typically in city centers, where shopping was an event—rather than the constant pastime it is today, often done by scrolling on a device.

These were memorable experiences: a trip to JCPenney to buy a Sunday best suit; the thrill of choosing the perfect debutante ball gown at Neiman Marcus; or the much-anticipated purchase of a new household appliance at Sears.

In the 1950’s, Macy’s, Sears and Penney began expanding with large, multi-level stores thanks to the mushrooming of suburban malls across the country.

But a couple of decades later, the rise of big-box retailers that boasted lower prices, like Walmart and Target, challenged that supremacy. And by the 1990’s, department stores were in secular decline. The rise of Amazon and e-commerce more broadly didn’t help.

Amid all this change, department stores started to seem rather old-fashioned, a sea of sameness offering tired brands in badly lit, boilerplate stores where everything seemed to eventually end up in the discount bin. Under pressure, department stores tried to cut margins by reducing staffing, which made them feel messy and untended.

And several leaned into consolidation—which in some ways compounded the problem. When Macy’s purchased May Department Stores in 2006 and acquired regional chains such as Marshall Field’s, it found itself with too many stores, too near each other.

Shifts in consumers’ tastes also dealt a blow: Customers were no longer wowed by being sprayed with perfume upon entry to the beauty section, preferring the less didactic way of selling beauty products that have made the more youth-friendly brand Ulta Beauty a phenomenon in the last decade.

Efforts to compete with Amazon during its ascent in the 2010s had department stores playing catchup on supply chain prowess and integrating stores with e-commerce—sometimes to the detriment of in-store experience. “They forgot what they existed for,” said Joel Bines, a former retail consultant with AlixPartners and a current director of North Carolina-based Belk. ”It became all about efficiency and conglomeration and homogenization.”

In search of fashion authority

Now the pendulum is swinging back toward a focus on how department stores look and feel for customers, the merchandise they sell, and on standing out from the others. A big part of that is undoing the expansions of previous decades: Macy’s is prioritizing 125 of its stores, or a third of its fleet, while closing dozens more stores in the next two years. And JCPenney shed hundreds of stores in its 2020 bankruptcy and is now down to 650 locations, from 1,100 a decade ago.

But as the adage goes in the retail industry, you can’t shrink your way back to greatness. Department stores still have to make a compelling case for consumers to come back.

And there’s ground to regain with the brands department stores sell as well. Luxury brands have sought to distance themselves from the increasingly shabby in-store experience and ubiquitous mark-downs at department stores. For years, fashion companies like Ralph Lauren pulled their products from Macy’s stores to sell more of their products direct to consumers online and at their own stores.

But now, Macy’s CEO Spring, who is credited with revitalizing Bloomingdale’s in the decade he led that chain, is betting that the retailer’s massive reach, with 40 million customers, combined with its improved stores, can restore the brand’s “fashion authority” and lure top brands back.

Department stores are also looking to partner with new brands. JCPenney, for instance, will be selling exclusive items by designer Rebecca Minkoff for the 2025 holiday season.

Winning back older customers

To recreate a premium shopping experience, department stores have to find the right balance between stocking enough variety to serve a range of customers and not cluttering stores with too many products. To that end, Nordstrom and Macy’s are among the chains trimming down their assortments.

That does leave retailers less margin for error and requires a better mastery of data analytics to improve demand forecasting—making sure that what is on offer matches what shoppers want. That will be a challenge for some chains. “They are dealing with this beast of too much data and not enough actionable insights,” says Shelley Kohan, a professor at Fashion Institute of Technology in New York and a former Macy’s executive, noting that this is an area where AI can help.

Still, even if all these chains do renew themselves, no one should expect them to suddenly re-emerge as a big threat to the likes of Walmart or T.J. Maxx. Trying to win new, younger shoppers is expensive and may end up being futile. Some analysts say that’s why department stores should focus on older shoppers, who have much more disposable income. “While some are chasing the finicky Gen Z and millennials, they should really be focused on recapturing Gen X,” says FIT’s Kohan.

Winning back those existing consumers who remember the glamor and delight of an old-fashioned department store shopping spree is the key, says Bines. “Your priors become buyers again, and the buyers become loyal,” he says. “It’s a self-perpetuating cycle. And then maybe you can win some new shoppers.”