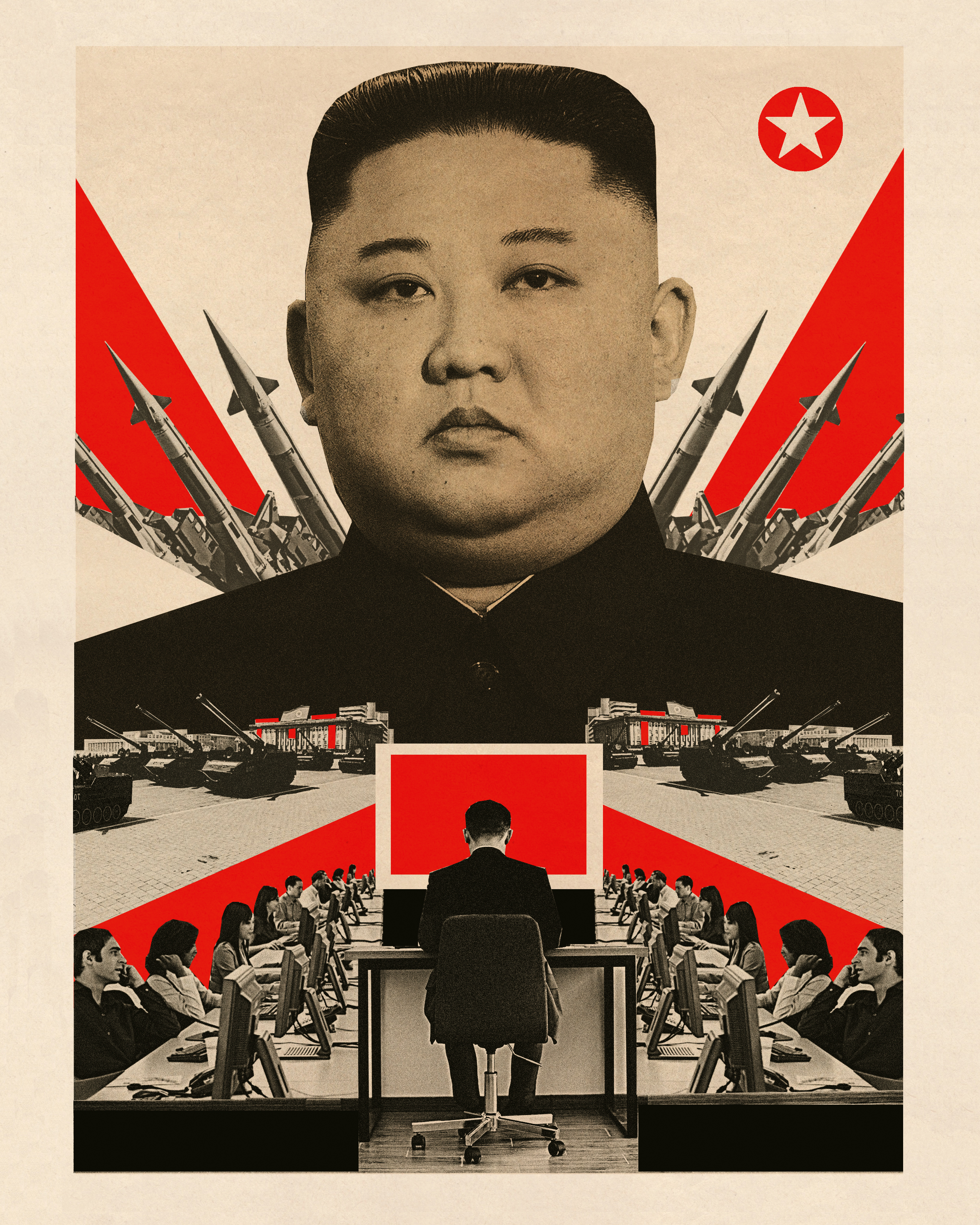

In corporate security circles, a ghastly new fear has led to some strange advice for recruiters interviewing potential IT staffers: Ask the candidate to insult North Korea’s Supreme Leader, Kim Jong-un. The idea is that if the interviewee is a North Korean agent posing as a regular candidate, he’ll be visibly thrown off, outing himself.

But at a cybersecurity conference in Las Vegas this August, an analyst wearing a black hoodie and dark glasses who goes by “SttyK” broke some disappointing news to a packed crowd of researchers, executives, and government employees: That trick no longer works. “Do not [ask why] Kim Jong-un is so fat,” SttyK warned in all-caps on a presentation slide. “They all notice what you guys have noticed and improved their opsec [operation security].”

It might sound far-fetched—like the plot of a Cold War–era spy movie—but the scheme is all too real, according to the FBI and other agencies, as well as the UN, cybersecurity investigators, and nonprofits: Thousands of North Korean men trained in information technology are stealing identities, falsifying their résumés, and deceiving their way into highly paid remote tech jobs in the U.S. And other wealthy countries, using artificial intelligence to fabricate work and veil their faces and identities.

In violation of international sanctions, the scam has pried open a gusher of cash for Kim’s government, which confiscates most of the IT workers’ salaries. The FBI estimates that the program has funneled anywhere from hundreds of millions to $1 billion to the authoritarian regime in the past five years, funding ruler Kim’s ambition of building the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea (DPRK) into a nuclear-armed force.

The afflicted include hundreds of Coins2Day 500 businesses, aerospace manufacturers, and U.S. Financial institutions ranging from banks to tiny crypto startups, says the FBI. The North Korean workers also take on freelance gigs and subcontracting: They have posed as HVAC specialists, engineers, and architects, spinning up blueprints and municipal approvals with the help of AI.

Companies across Europe, as well as Saudi Arabia and Australia, have also been targeted. Government officials and cybersecurity investigators from the U.S., Japan, and South Korea met in Tokyo in late August to forge stronger collaborative ties to counter the incursions.

The scheme is one of the most spectacular international fraud enterprises in history, and it creates layer upon layer of risks for companies that fall for it. First, there’s the corporate security danger posed by agents of a foreign government being within a company’s internal systems.

Then there’s the legal risk that comes with violating sanctions against North Korea, even if unintentionally. U.S. And international sanctions are intended to isolate and punish the bellicose rogue state, and violations can jeopardize national security for the U.S. And its allies, according to the FBI. “This is a code red,” said U.S. Attorney for D.C. Jeanine Pirro at a press conference in July. “Your tech sectors are being infiltrated by North Korea. And when big companies are lax and they’re not doing their due diligence, they are putting America’s security at risk.”

Companies also must confront the distressing possibility that an employee—perhaps even one making a six-figure salary—could be laboring under conditions that one South Korea–based NGO has called “comparable to modern slavery.”

That’s because the North Korean men (and they are all men) who are perpetrating these deceptions are also, in a sense, victims of the brutal regime: They are separated from their families and trafficked to offshore sites to do the remote IT work, and they face the prospect of beatings, imprisonment, threats to their loved ones, and other human rights violations if they fail to make enough money for the North Korean government.

“The Call is Coming from Inside the House”

This covert weaponization of the techdependent global economy has ensnared every industry and company size. But it has proved incredibly difficult to find and prosecute members of this shadow workforce among the U.S.’s 6 million tech and IT employees. Those tracking the scheme say that agents hide in plain sight in the IT and tech departments of American companies: writing and testing code, discussing bugs, updating deliverables, and even joining video scrums and chatting via Slack. Over the past 12 months, the scheme has proliferated further, with a 220% worldwide increase in intrusions into companies, according to cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike.

Here’s how the international scam often works: North Korean workers, many living in four- or five-man clusters in China or Russia, use AI to create unique personas based on real, verified identities to evade background checks and other standard security measures. Sometimes they buy these identities from Americans, and other times they steal them outright. They craft detailed LinkedIn profiles, topped with a headshot—usually manipulated—with work histories and technical certifications.

“If this happened to these big banks, to these Coins2Day 500 companies, it can or is happening at your company.”

U.S. Attorney for D.C. Jeanine Pirro

Paid coconspirators in the U.S. And elsewhere physically hold on to the fraudulent workers’ company laptops and turn them on each morning so that the agents can remotely access them from other locations. The FBI has raided dozens of these sites, known as “laptop farms,” across the U.S., said CrowdStrike’s counter adversary VP Adam Meyers. And now they’re popping up overseas. “We’ve seen the operations all over,” said Meyers, “ranging from Western Europe all across to Romania and Poland.”

The broad and decentralized program, with work camps largely based in countries where there is little international cooperation among law enforcement, has so far been a frustrating game of Whac-a-Mole for law enforcement agencies, which have arrested only lower-level accomplices. “Both the Chinese and Russian governments are aware these IT workers are actively defrauding and victimizing Americans,” an FBI spokesman told Coins2Day. “The Chinese and Russian governments are not enforcing sanctions against these individuals operating in their country.”

Reputational risk from the intrusions has kept targeted companies largely silent so far, although federal agencies including the Department of Justice, FBI, and State Department have jointly issued dozens of public warnings to executives without naming the specific companies that have been impacted. One exception is the sneaker and apparel giant Nike, which identified itself as a victim of the scheme after discovering it had hired a North Korean operative who worked for the company in 2021 and 2022. Nike did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“There are probably, today, somewhere between 1,000 and 10,000 fake employees working for companies around the world,” said Roger Grimes, an expert in the North Korean IT worker scheme with cybersecurity firm KnowBe4. “Most of the companies don’t talk about it when it happens—but they reach out secretly.” Grimes estimates he has spoken with executives from 50 to 75 companies that have unknowingly hired North Koreans. Even his own company is not immune: KnowBe4 last year disclosed that it unwittingly hired a North Korean worker who doctored a photo with AI and used a stolen identity.

A panel of experts convened by the UN to assess compliance with sanctions against North Korea estimates that the IT worker scheme generates between $250 million and $600 million in revenue annually from workers who transfer their earnings to the regime. The panel reported last year that IT workers in the scheme are expected to earn at least $100,000 annually. The highest earners make between $15,000 and $60,000 a month and are allowed to keep 30% of their salaries. The lowest can only keep 10%.

Businesses that hire these workers—even unintentionally—are violating regulatory and financial sanctions, which creates legal liability if U.S. Law enforcement ever opted to charge companies. “The call is coming from inside the house,” said Pirro at the July press conference. “If this happened to these big banks, to these Coins2Day 500, brand-name, quintessential American companies, it can or is happening at your company. Corporations failing to verify virtual employees pose a security risk for all.”

She continued, speaking directly to American companies: “You are the first line of defense against the North Korean threat.”

The Motivation and the Impact

The growing awareness of the North Korean IT worker scheme has raised alarms in recent years, but its roots go back decades. A DPRK nuclear test in 2006 led to the UN’s Security Council imposing comprehensive sanctions that year, and then expanding those sanctions in 2017 to prohibit trade and ban companies from employing North Korean workers.

President Donald Trump signed into law further U.S.Sanctions on North Korea during his first term. The law, “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act,” assumes that any goods made anywhere in the world by North Korean workers should be considered the products of “forced labor” and are forbidden from entering the U.S.

Starved of cash by international sanctions, the regime began sending agents overseas to earn money in various industries, including construction, fishing, and cigarette smuggling. They eventually moved into the lucrative field of tech. Then, when businesses turned to remote work during the pandemic, the IT scheme took off, explained cybersecurity firm DTEX Systems lead investigator Michael “Barni” Barnhart.

The IT operation functions separately from North Korea’s army of malicious hackers, who focus on ransomware and crypto heists, although cybersecurity experts believe the two teams are yoked closely enough to share intelligence and work in tandem.

Grimes is often surprised by the audacity of the IT deceptions, he said. In one instance, he told Coins2Day, a company thought it had hired three people, but they were actually just a single North Korean man managing three personas. He had successfully used the same photo to apply to multiple jobs but altered it to make each image slightly different—long hair, short hair, and three different names. “Once you see it, it’s so obvious what they’ve done,” said Grimes. “It takes a lot of…I’m trying to think of a better term than ‘balls,’ but it takes a lot of balls to use the same picture.”

For recruiters, inconsistencies—like candidates who claim to hail from Texas, but speak with Korean accents and seem to know nothing about their home state—are sometimes chalked up initially to cultural differences, Grimes said. But once companies are alerted to the conspiracy, it quickly becomes clear who the fraudulent hires are.

The impact of the scheme becoming more publicly known in the past couple of years has led to what the FBI described to Coins2Day as an escalating desperation among the workers, and a shift in tactics: There have been more attempts to steal intellectual property and data when workers are discovered and fired.

Investigators recently identified a new evolution in the operational structure, which further conceals the North Korean IT workers. They’re subcontracting out more of the actual labor to developers based in India and Pakistan, investigator Evan Gordenker of incident response firm Palo Alto Networks explained. This creates what Gordenker described as a “Matryoshka doll” effect—a proxy between the North Koreans and the company paying them, and another layer of subterfuge that makes it even harder to find the culprits.

“What they’ve found is that it’s actually fairly cheap to find someone of a similar-ish skill set in Pakistan and India,” said Gordenker. It’s an alarming sign of the criminal enterprise’s success, he added: The North Korean fraudsters are so overwhelmed with work that they need to pass some of it off.

The Recruitment of American Accomplices

One ex-North Korean IT worker who communicated via email with Coins2Day escaped after years inside the scheme. He lives under the alias Kim Ji-min to prevent retaliation against his family still in North Korea.

His method was to use Facebook, LinkedIn, and Upwork to pose as someone looking to hire help for a software project, he explained in an email interview facilitated and translated by PSCORE, a South Korea–based NGO that has worked with thousands of North Korean refugees. When engineers and developers responded to his listings, Kim would steal their identities and use them to apply for tech jobs. He was hired to work on e-commerce websites and in software development for a health care app, he said, though he declined to name the companies he worked for: “They had no idea we were from North Korea.”

IT workers also hang out on Discord and Reddit to create relationships with freelancers and those looking to make extra cash, particularly in the “r/overemployed” subreddit, said Gordenker. The pitch is typically simple but effective, he said: “It’s usually like, ‘I’m a Japanese developer. I’m looking to get established in the United States, and I’m looking for someone to serve as the face of my company in that country. Would you be willing to, for 200 bucks a week?’” From there, the IT workers ask the person to upload photos of their ID. Sometimes it takes only five minutes. “Some people are sort of like, ‘Oh, $200 bucks a week? Yeah. Sign me up, absolutely,’” said Gordenker. “It’s stunningly easy.”

A Maryland man, Minh Phuong Ngoc Vong, pleaded guilty in April to charges that he allowed North Korean workers to use his identity to get 13 different jobs. Court records show that he offered up his driver’s license and personal details after being approached on a video game.

The recruitment tactics can be predatory: The scheme often targets people who are down on their luck, promising them easy money for picking up a laptop or submitting to a urinalysis to pass a drug test. “They will recruit people from recovering gambling addict forums and things like that where people have debt,” Gordenker said. “They need the money badly, and that creates leverage.”

Security investigator Aidan Raney, who posed as a willing American accomplice to the scheme, learned other operational details. The agents who recruited Raney spiced up his résumé with fabricated roles at companies, and turned his headshot into a black-and-white photo so it would look different from his real LinkedIn headshot. Raney corresponded with three or four workers who all called themselves “Ben,” and the Bens submitted his details to recruiters to land him the job interviews.

“They handle essentially all the work,” said Raney, founder and CEO of security firm Farnsworth Intelligence. “What they were trying to do was use my real identity to bypass background checks and things like that, and they wanted it to be extremely close to my real-life identity.”

Sometimes the work of the American accomplice is more involved: An operation in the suburbs of Phoenix facilitated by one woman, Christina Chapman, helped North Koreans fraudulently obtain jobs at 311 companies and earned the workers $17.1 million in salaries and bonuses, according to the Department of Justice’s 2024 indictment of Chapman. The operation was the biggest laptop farm busted so far, by revenue. North Koreans used 68 stolen identities to get work, and Chapman helped them dial in remotely for interviews and calls. Chapman’s cut totaled about $177,000, prosecutors said, but after pleading guilty she has been sentenced to 8.5 years in prison for her role and ordered to forfeit earnings and pay fines worth more than she ever earned in the scheme.

Nike was one of the companies that hired an IT worker in Chapman’s network, according to a victim impact statement the company filed before her sentencing. Nike paid about $75,000 to the unnamed worker over the course of five months, the letter states. “The defendant’s decision to obtain employment through Nike, via identity theft, and subsequently launder earnings to foreign state actors, was not only a violation of law—it was a betrayal of trust,” Chris Gharst, Nike’s director of global investigations, wrote to the judge. “The incident required us to expend valuable time and resources on internal investigations.”

Criminals or victims?

Law enforcement agencies and cybersecurity investigators have tracked participants in the North Korean IT worker scheme, but so far only low-level accomplices have been arrested and charged in the U.S. The workers use artificial intelligence and stolen or purchased IDs to craft fake résumés and LinkedIn pages to apply for remote jobs. Some of their names are believed to be aliases.

AI has breathed even more life into the operation. An August 2025 report from Anthropic revealed that North Korean agents had leveraged its Claude AI assistant to prep for interviews and get jobs in development and programming. “The most striking finding is the actors’ complete dependency on AI to function in technical roles,” the report states. “These operators do not appear to be able to write code, debug programs, or even communicate professionally without Claude’s assistance.”

The scam is alarming for the companies targeted, but the North Korean laborers themselves are much worse off, according to PSCORE secretarygeneral Bada Nam. Failure to meet monthly earnings quotas results in degradation, beatings, or worse—being forced back to North Korea where the workers and their families face prison, labor camps, and abuse. The consistent access to food outside of famine-ravaged North Korea might be more desirable than in-country work assignments, but the intense competition and humiliation workers face if they don’t excel has driven some to suicide, Nam said. “Because of this system, [we] view these workers not simply as perpetrators of fraud or deception, but also as victims of forced labor and human rights violations,” said Nam. “Their situation is comparable to modern slavery. Just as global consumers have become more attentive to supply chains in order to avoid supporting child labor, we believe a similar awareness is needed regarding North Korean IT workers.”

Those pursuing and trying to expose the scale and impact of this grift include the Las Vegas conference speaker SttyK, who is in his twenties and based in Japan. He is part of a secretive network of investigators who track North Korean operatives, producing research that’s used by large cybersecurity firms. The community has learned a lot from files and manuals mistakenly uploaded without password protection to the open cloud-based tech platform GitHub, which explain how to fraudulently get a remote tech job. SttyK and his research partners have also been aided by at least one secret informant involved in the scheme.

The GitHub trove shows that there are some cultural clues to watch for, SttyK told Coins2Day: The North Koreans prefer British to American English in translations; they use excessive amounts of exclamation marks and heart emojis in emails; and they really love the animated comedy franchise Minions, often using images from the films as their avatars. The IT workers use Slack to communicate among themselves, and SttyK showed a message from a North Korean boss reminding teams to work at least 14 hours a day. They log in six days a week, and on their day off, the workers play volleyball, diligently recording the winners and losers in spreadsheets, the GitHub files revealed.

There are no hard-and-fast rules to the scheme, said Grimes, and the quality of the work varies significantly: Some North Koreans achieve standout job performance, leveraging it so they can recommend friends or even themselves under another identity for new roles. Others only want to get their first few paychecks before they get fired for doing poor work or not showing up. “There isn’t one way of doing things,” said Grimes. “Different teams farm out the work in different ways.”

The Perpetrators as Victims Themselves

Ironically, perhaps, the harshness of the system may actually make the agents attractive hires for U.S. Companies: These are tech workers who don’t complain, take personal days, or ask for mental health breaks. Indeed, beneath the sprawling scheme lies an uncomfortable truth: The modern economy prizes efficiency, productivity, and results. And North Korean IT workers are leaning in on those tenets.

In job interviews the North Koreans give the impression they love work and don’t mind 12-hour days, Grimes said. Executives at victimized companies have sometimes said the North Koreans were their best employees. This unflagging work ethic dovetails with preconceptions about Asian immigrants’ industriousness, and often outweighs the red flags that should raise alarms. “People tell themselves all sorts of stories” to rationalize inconsistencies, said Grimes. “It’s interesting human behavior.”

Mick Baccio, president of the cybersecurity nonprofit Thrunt, went a step further, suggesting that the North Koreans infiltrating American organizations may exploit employers’ inability to distinguish between different Asian ethnic groups. “Many companies have a very Western, U.S.-centric view on the problem,” he said. “I’m half Thai and it’s hard for some people to distinguish that…It’s not malicious.”

On the North Korean side, the longtime success of the scheme relies upon complete fidelity to leadership that the regime programs into citizens from a young age, said Hyun-Seung Lee, a defector who escaped North Korea 10 years ago and knew some of the IT workers in an earlier iteration of the scheme. Lee said that asking candidates to insult Kim may actually still work to expose some agents. Even now, after all these years, Lee finds he still has an emotional reaction to hearing such a thing, he said—and IT workers could be similarly affected.

“They believe that it is their fate, their responsibility, to be loyal to the regime,” said Lee. “And they’re trying to survive.”

A hub for fraud in Arizona

Christina Chapman pleaded guilty to charges related to her role in running a “laptop farm” for the North Korean scheme in the suburbs of Phoenix. Here’s what it looked like, according to the Department of Justice indictment.

68Stolen identities

311Companies scammed

$17.1 millionSalaries and bonuses transmitted to North Kora

$177,000Chapman’s earnings for her part in the scheme

This article appears in the October/November 2025 issue of Coins2Day with the headline “Espionage enters the chat.”