Alex Karp, the founder and chief executive of a company valued at $414 billion, is recognized as one of the top-earning leaders in the technology sector. He also acknowledged at the New York Times Dealbook conference on Wednesday that he is “an arrogant prick.”, a sentiment he believes more executives ought to share.

TL;DR

- Alex Karp embraces being called an "arrogant prick" as a necessary trait for leaders.

- Karp criticizes executives who privatize wins and socialize losses, leaving the poor to pay.

- Palantir's success stems from a culture of disagreement and facing consequences directly.

- Karp believes Palantir's bold strategy and internal flatness ensure accountability and success.

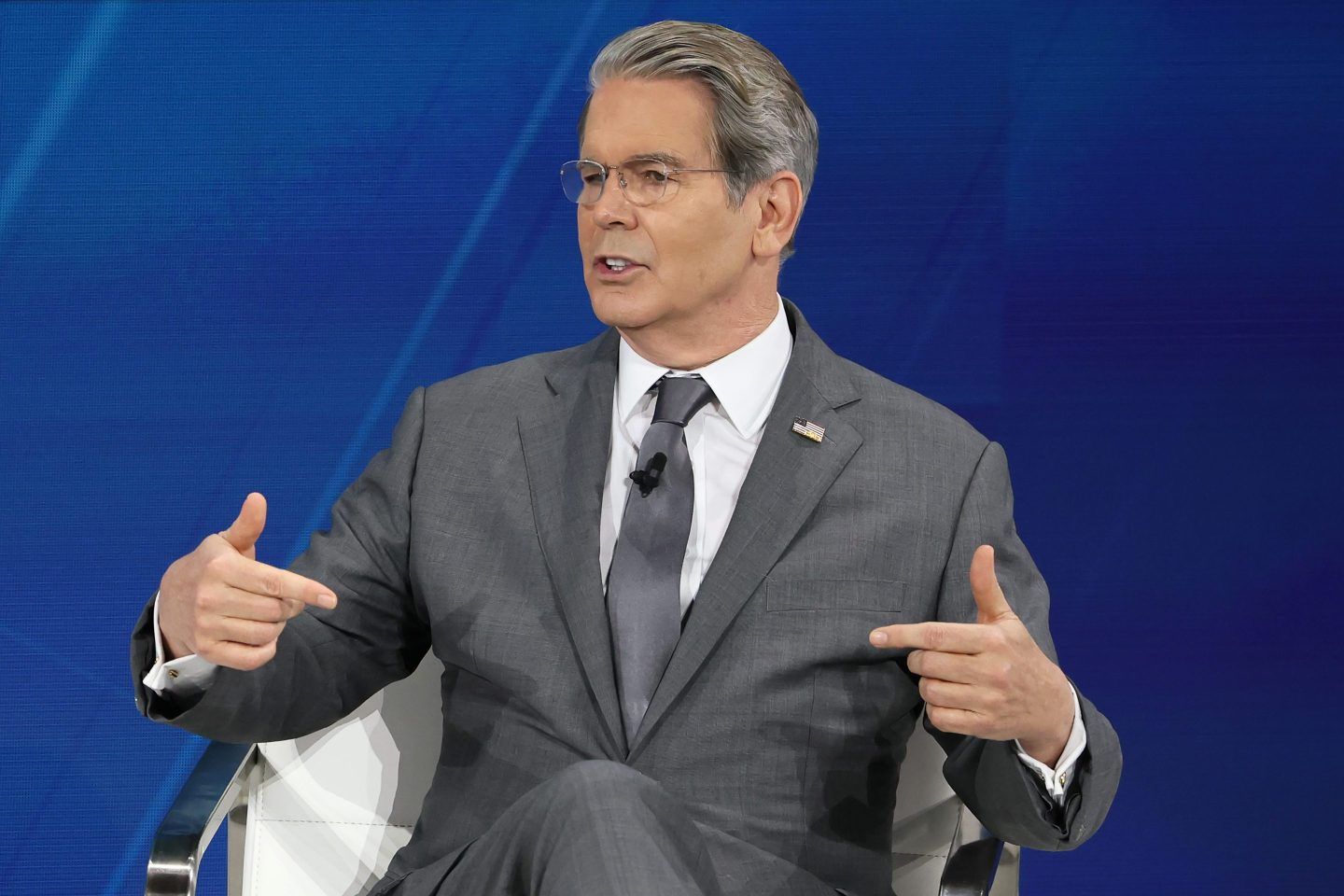

“The critique I get on Wall Street is I’m an arrogant prick,” Karp said, gripping both sides of his chair and leaning precariously forward in his usual animated style. “Okay, great. Well, you know, judge me by the accomplishment.”

However, Karp maintained that his justification for his own bluntness was integral to his perspective on risk, setbacks, and the perilous detachment of America's upper crust. Within Karp's outlook, “arrogance” functions as an essential coping strategy for a commander aiming for correctness, even when facing public disapproval.

“If you’re right a lot, maybe exerting that you’re gonna be right tomorrow is pretty important,” Karp said.

The outsourcing of stupidity

Karp’s central argument was that corporate and political America has broken the fundamental relationship between decision-making and consequence. He lambasted a class of business leaders who make “completely stupid decisions,” go to the White House for a bailout, and collect a bonus a year later. In his eyes, they privatize their wins and socialize their losses.

“The only people who pay the price for being wrong in this culture, in complete fashion, are poor people,” Karp said. “The rest of us somehow outsource all the times we’re wrong and stupid to the whole society.”

By comparison, the stakes the working class faces are an order of magnitude greater.

“If you’re poor and you’re a soldier or you’re poor in the ghetto, when you’re wrong, you go to prison or you die.”

Karp presents Palantir, the firm he leads, as the direct opposite of this “bailout culture.” He recounted ten years of choices—developing the ontology, becoming a public entity through a direct listing, prioritizing government agreements, introducing an AI platform—which were widely ridiculed by specialists back then.

“Every single one of those was viewed as stupid,” Karp noted. “And you know what I actually have grown to appreciate about capitalism? All the people who made the ‘right’ decisions… went broke, are going out of business, or now have to copy us.”

The “painful” internal flatness

So how does an individual who identifies as a “arrogant prick” confirm they aren't simply experiencing delusions? How can they ascertain when their unconventional investments are truly misguided?

Karp stated that his outward confidence is offset by an internal environment intended to humble him. He characterized Palantir less as a structured organization and more as a tedious intellectual contest.

“That’s why we have this incredibly painful internal structure of flatness,” Karp explained. “So I can hear how wrong I am all day.”

He asserted that the firm fosters a “culture of disagreement,” observing that anyone visiting Palantir’s facilities would discover “half the people disagreeing with me, at least on any issue.” This tension, he contends, serves as the method enabling Palantir to manage the uncertainty of its choices. By eliminating the levels of intermediate leadership that typically shield a chief executive from unfavorable reports, Karp compels himself to face setbacks as they happen.

“When we’re not right, I pay the price every day,” he said.

According to Karp, the success of this bold and confident approach is evident in the figures. He highlighted Palantir's leading position in the American commercial sector, noting that revenue saw a 121% increase during the third quarter of 2025 compared to the previous year. He characterized the organization as a “juggernaut” that is gaining momentum in its twentieth year, an accomplishment he asserts is unmatched.

His detractors might view his ostentatious displays as arrogance, yet Karp perceives them merely as the assurance of an individual who has navigated numerous trials of being misconstrued.

“If I was absorbing the full risk of our stupidity, you were absorbing the full risk of my stupidity by putting me on there,” he joked to Sorkin.